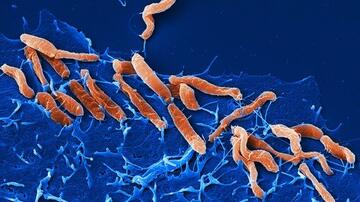

Helicobacter pylori: Signs of selection in the stomach

Helicobacter pylori, a globally distributed gastric bacterium, is genetically highly adaptable. The DZIF team of Professor Sebastian Suerbaum at LMU has now characterized its population structure in individual patients, demonstrating an important role of antibiotics for its within-patient evolution.

The cosmopolitan bacterium Helicobacter pylori is responsible for one of the most prevalent chronic infections found in humans. Although the infection often provokes no definable symptoms, it can result in a range of gastrointestinal tract pathologies, ranging from inflammation of the lining of the stomach to gastric and duodenal tumors. Approximately 1% of all those infected eventually develop stomach cancer, and the World Health Organization has classified H. pylori as a carcinogen. One of Helicobacter pylori’s most striking traits is its genetic diversity and adaptability. Researchers led by microbiologist Sebastian Suerbaum (Chair of Medical Microbiology and Hospital Epidemiology at LMU’s Max von Pettenkofer Institute) have now examined the genetic diversity of the species in the stomachs of 16 patients, and identified specific adaptations that enable the bacterium to colonize particular regions of the stomach. They were also able to demonstrate that antibiotic therapies reduce the degree of diversity of the H. pylori population and select for resistant variants. – Moreover, they showed that antibiotics prescribed for other infections can select for resistant strains of H. pylori and shape its population structure. The new findings appear in the online journal Nature Communications.

The remarkable degree of genetic flexibility exhibited by H. pylori in the course of a chronic infection has been investigated in several previous studies. However, little has been learned hitherto about how this capacity for variation is expressed in individual patients at specific times after infection. The stomach is conventionally divided into three main anatomical regions, which are differentiated by their physiology and function, providing ecological niches for different subpopulations of H. pylori. “Using samples obtained from different regions of the stomach, we asked how strongly the H. pylori strains differed within each patient,” Suerbaum says. “To do so, we isolated at least 20 strains of bacteria from each patient and analyzed their genomes by a variety of sequencing methods.”

The results showed that H. pylori is indeed capable of adapting to the specific conditions that prevail in each of the anatomically defined regions of the stomach. This adaptability can be found, for example, in gene families that code for the organism’s outer membrane proteins, which serve to attach it to the gastric epithelium in its human hosts. “We also detected signatures of selection and adaptation among sets of genes that are required for bacterial motility and chemotaxis,” says Dr. Florent Ailloud, a postdoc in Professor Suerbaum’s group and first author of the study.

In addition, the use of antibiotics was found to have a significant impact on the genetic diversity of H. pylori. This phenomenon was especially striking in one particular patient who took part in the study. At the initial sample from this individual, the H. pylori population was highly diverse and showed no signs of resistance to any of the antibiotics tested during growth in the laboratory. However, in a sample collected 2 years later, the level of diversity within the population was extremely low, and the bacteria had become completely resistant to a frontline antibiotic. Over the course of the intervening 2 years, the population had apparently undergone a massive reduction in size, which set the scene for the subsequent large-scale change in the structure of the surviving population. In fact, the researchers found that exposure to antibiotics had a profound impact on all the Helicobacter populations they studied. “As a rule, application of the most appropriate combination of antibiotics is essential to completely eradicate H. pylori from the stomach and prevent the emergence of resistance. However, it is now becoming apparent that antibiotics have had a huge impact on the evolutionary dynamics of the species as a whole in recent decades, as antibiotics have become readily available, and are increasingly employed, all over the world,” Suerbaum concludes.

The new study was carried out in cooperation with the National Reference Center for Helicobacter pylori, which is led by Sebastian Suerbaum and has been based at LMU’s Max von Pettenkofer Institute since January 2017, the clinical team led by Peter Malfertheiner at Magdeburg University and LMU, Warwick University in Coventry (UK), the Leibniz Institute-DSMZ in Braunschweig and other collaborating partners in Germany and abroad. The project was supported by funding allocated to the Collaborative Research Center CRC 900 on “Microbial Persistence and its Control” and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF).